If you build extensions long enough, you eventually get burned by a dependency you didn’t mean to create: another app starts calling into your “helper” codeunit, or relies on a table/field you never intended as public API. Later, you refactor—and everything breaks.

That’s the real value of the Access property: it lets you define (at compile time) what’s part of your supported surface area versus what’s strictly internal implementation.

What Is the Access Property?

The Access property sets the compile-time visibility of an AL object (and, for tables, of individual fields). In practice, it controls whether other AL code can take a direct reference to that symbol.

Think of it as the AL equivalent of “public vs internal” in other languages, but scoped to apps (modules) and extension objects.

What the Access Property Applies To

Access applies to:

- Codeunit

- Query

- Table

- Table field

- Enum

- Interface

- PermissionSet

Object-Level Access: Public vs Internal

For most objects (tables, codeunits, queries, interfaces, enums), you’ll typically use:

Access = Public;(default): Other apps that reference your app can use the object.Access = Internal;: Only code inside your app can reference the object.

Example: keep a table internal so nobody else compiles against it:

table 50111 "DVLPR Internal Staging"

{

DataClassification = CustomerContent;

Access = Internal;

fields

{

field(1; "Entry No."; Integer) { }

field(2; Payload; Blob) { }

}

}

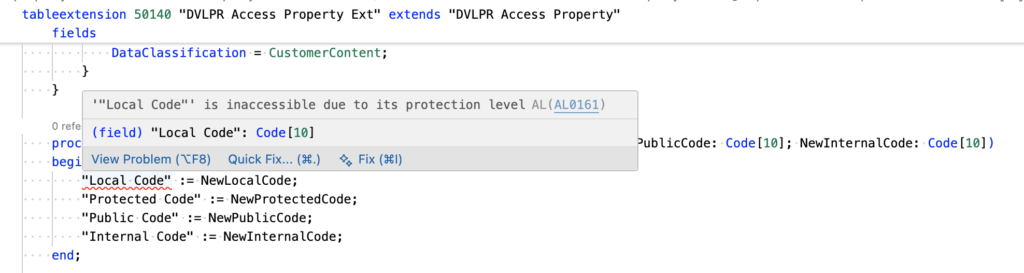

Table Field Access: Local, Protected, Internal, Public

Table fields add two extra options that are incredibly useful for designing clean extensibility:

Local: Only code in the same table or the same table extension object where the field is defined can reference the field.Protected: Code in the base table and table extensions of that table can reference the field.Internal: Anything inside the same app can reference the field.Public(default): Any referencing app can reference the field.

Example: Table with different field access levels:

table 50140 "DVLPR Access Property"

{

Access = Public;

Caption = 'DVLPR';

DataClassification = CustomerContent;

fields

{

field(1; "Code"; Code[10])

{

Caption = 'Code';

ToolTip = 'Specifies the value of the Code field.';

}

field(2; "Local Code"; Code[10])

{

Access = Local;

Caption = 'Local Code';

ToolTip = 'Specifies the value of the Local Code field.';

}

field(3; "Protected Code"; Code[10])

{

Access = Protected;

Caption = 'Protected Code';

ToolTip = 'Specifies the value of the Protected Code field.';

}

field(4; "Public Code"; Code[10])

{

Access = Public;

Caption = 'Public Code';

ToolTip = 'Specifies the value of the Public Code field.';

}

field(5; "Internal Code"; Code[10])

{

Access = Internal;

Caption = 'Internal Code';

ToolTip = 'Specifies the value of the Internal Code field.';

}

}

keys

{

key(PK; "Code")

{

Clustered = true;

}

}

}

The Access levels for table fields are especially useful when you want to allow controlled extensibility without opening up everything.

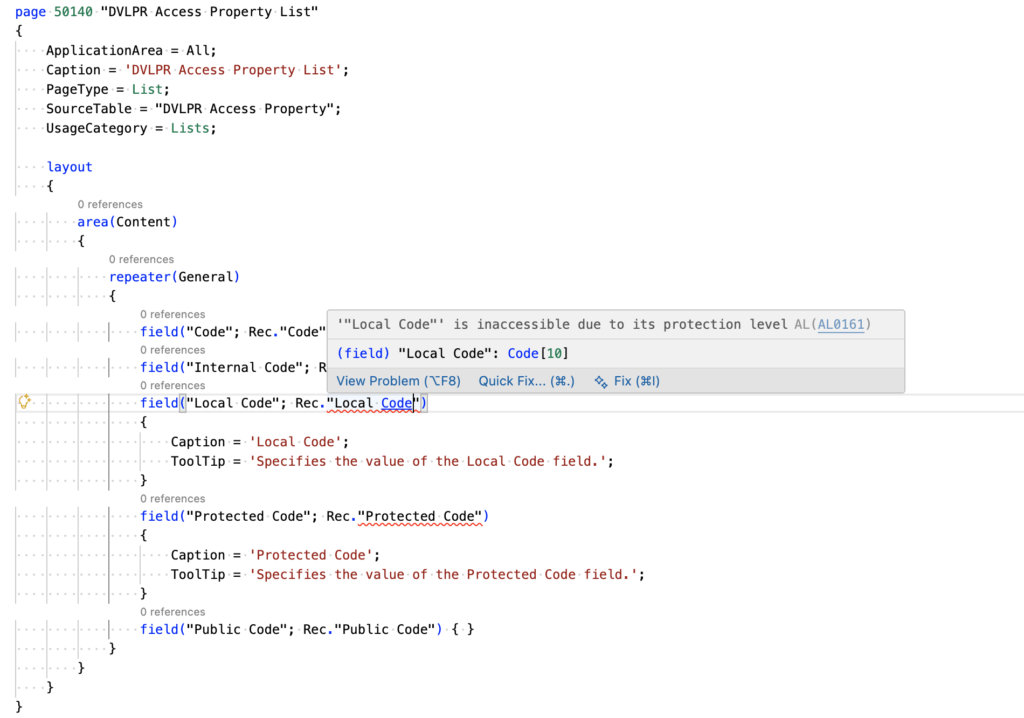

If, for example, you have a field with Access = Local, you won’t be able to reference it by name from a page, report, or codeunit—even inside the same app.

One more practical detail from the platform: table and field accessibility affects the in-client Designer. Only Public table fields can be added to pages using Designer.

Sharing Internals Between Your Own Apps: internalsVisibleTo

Sometimes you do want internals shared—but only with your own “companion” apps. That’s where internalsVisibleTo in app.json comes in.

It allows specific friend modules to compile against your Access = Internal objects.

Example app.json snippet:

{

"internalsVisibleTo": [

{

"id": "00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000",

"name": "DVLPR Companion App",

"publisher": "DVLPRLIFE"

}

]

}

Important: Access Is Compile-Time Only (Not Security)

This is the part that’s easy to misunderstand.

Access is enforced at compile time. It is not a runtime security boundary.

One way to think about it: Access controls who can compile against your symbols, not who can ultimately interact with data at runtime. Business Central still has reflection-style mechanisms (such as RecordRef, FieldRef, and TransferFields) that can work with tables/fields without a direct symbol reference.

For example, even though the Local Code field is marked as Access = Local, you can still technically read and write it using RecordRef and FieldRef (because those APIs work by field number rather than a compile-time field reference):

procedure GetLocalCode(): Code[10]

var

RecordRef: RecordRef;

FieldRef: FieldRef;

LocalCode: Code[10];

begin

RecordRef.GetTable(Rec);

FieldRef := RecordRef.Field(2);

LocalCode := FieldRef.Value;

RecordRef.Close();

exit(LocalCode);

end;

procedure SetLocalCode(NewLocalCode: Code[10])

var

RecordRef: RecordRef;

FieldRef: FieldRef;

begin

RecordRef.GetTable(Rec);

FieldRef := RecordRef.Field(2);

FieldRef.Value := NewLocalCode;

RecordRef.Modify();

RecordRef.Close();

end;

When I Reach for Each Level

My personal defaults:

Public: Objects/fields I’m willing to support as a stable contract.Internal: Implementation objects I expect to refactor freely.Protected(fields): When I want controlled extensibility throughtable extensions.Local(fields): Fields that are strictly internal to the table logic.

Wrapping Up

The Access property is one of the most practical tools you have for keeping an extension maintainable over time. It helps you draw a clear line between API and implementation, reduces accidental coupling between apps, and makes your intent obvious to anyone reading your symbols.

Learn more about access modifiers here.

Learn more about the Access property here.

Learn more about internalsVisibleTo in the app.json schema here.

Note: The code and information discussed in this article are for informational and demonstration purposes only. The Access property is available from runtime version 4.0.